Transfer Learning in Natural Language Processing

Applying transfer learning on language models (ULMFit)

- Universal Language Modeling

- Averaged Stochastic Gradient Method (ASGD) Weight Dropped Long Short Term Memory Networks (AWD-LSTM)

- ULMFit

- Results

The following article first appeared on Intel Developer Zone.

Universal Language Modeling

People have been using transfer learning in computer vision (CV) for a considerable time now, and it has produced remarkable results in these few years. In some tasks, we have been able to surpass human level accuracy as well. These days, implementations that don’t use pretrained weights to produce state-of-the-art results are rare. In fact, when people do produce them, it’s often understood that transfer learning or some sort of fine-tuning is being used. Transfer learning has had a huge impact in the field of computer vision and has contributed progressively in advancement of this field.

Transfer Learning was kind of limited to computer vision up till now, but recent research work shows that the impact can be extended almost everywhere, including natural language processing (NLP), reinforcement learning (RL). Recently, a few papers have been published that show that transfer learning and fine-tuning work in NLP as well and the results are great.

Recently OpenAI also had a retro contest in which participants were challenged to create agents that can play games without having access to the environment which was used to train it using transfer learning. It’s now possible to explore the potential of this method.

Leveraging past experiences to learn new things (new environments in the context of RL)

Leveraging past experiences to learn new things (new environments in the context of RL)

Previous research involved incremental learning in computer vision, bringing generalization into models since it’s one of the most important components in making learning in neural networks robust. One paper that aims to build on this is Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification.

Text classification is an important component in NLP concerned with real-life scenarios such as bots, assistants, fraud or spam detection, document classification, and more. It can almost be extended to pretty much any task since we’re dealing with Language Models. This author has worked with text classification, and until now much of the academic research still relies on embeddings to train models like word2vec and GloVe.

Limitations of Embeddings

Word embeddings are dense representation of words. Embedding is done by using real-valued numbers that have been converted into tensors, which are fed into the model. A particular sequence needs to be maintained (stateful) in this model so that the model learns syntactic and semantic relationships amongst words and context.

Visualization of different types of data

Visualization of different types of data

When visualized, words with closer semantic meaning would have their embeddings closer to each other, enabling each word to have varied vector representation.

Words that Occur Rarely in Vocabulary

When dealing with datasets, we usually come across words which aren’t there in the vocabulary since we have a limitation on how many words we can have in memory.

*Tokenization; These words exist in vocabulary and are common words but with embeddings token like

*Tokenization; These words exist in vocabulary and are common words but with embeddings token like

For any word that appears only a handful of times, this model is going to have a hard time figuring out semantics of that particular word, so a vocabulary is created to address this issue. Word2vec cannot handle unknown words properly. When a word is not known, its vector cannot be deterministically constructed, so it must be randomly initialized. Commonly faced problems with embeddings are:

Dealing with Shared Representations

Another area where this representation falls short is that there is no shared representation among subwords. Prefixes and suffixes in English often add a common meaning to all of them (like -er in “better” and “faster”). Since each vector is independent, the semantic relationships among words cannot be fully realized.

Co-Occurrence Statistics

Distributional word-vector models capture some aspects of co-occurrence statistics of the words in a language. Embeddings which are trained on word co-occurrence counts can be expected to capture semantic word similarity, and hence can be evaluated based on word-similarity tasks.

If a particular language model takes char-based input that cannot benefit from pretraining, randomized embeddings would be required.

Support for New Languages

Making use of embeddings will not make this model robust when confronted with other languages. With new languages, new embedding matrices would be required that cannot benefit from parameter sharing, so model cannot be used to perform cross-lingual tasks.

Embeddings can be concatenated, but training for this model must still be given from scratch; pretrained embeddings are treated as fixed parameters. Such models are not useful in incremental learning.

As computer vision has already shown, hypercolumns are not useful as compared to other prevalent training methods. In CV, hypercolumn of a pixel are vectors of activations of all ConvNet units above that pixel.

Figure 4. Hypercolumns in ConvNets(Source)

Figure 4. Hypercolumns in ConvNets(Source)

Averaged Stochastic Gradient Method (ASGD) Weight Dropped Long Short Term Memory Networks (AWD-LSTM)

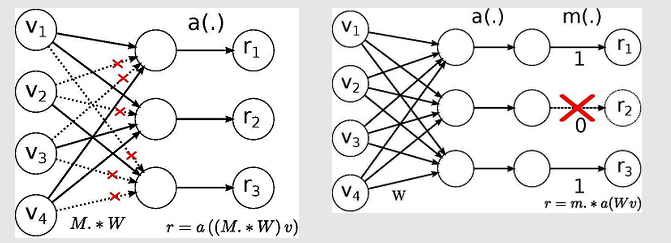

The model used in this research is heavily inspired from this article: Regularizing and Optimizing LSTM Language Models. It makes use of the weight-dropped LSTM that uses DropConnect on hidden-to-hidden weights as form of recurrent regularization. DropConnect is a generalization of Hinton’s Dropout for regularizing large fully connected layers within neural networks.

When training with Dropout, a randomly selected subset of activations is set to zero within each layer. DropConnect sets a randomly selected subset of weights within the network to zero. Each unit thus receives input from a random subset of units in the previous layer.

Differences between DropConnect and Dropout

Differences between DropConnect and Dropout

By making use of DropConnect on the hidden-to-hidden weight matrices—namely [Ui , Uf , Uo , Uc ] —within the LSTM, overfitting can be prevented on the recurrent connections of the LSTM. This regularization technique would also help prevent overfitting on the recurrent weight matrices of other Recurrent Neural Network cells.

Commonly used set of values:

dropouts = np.array([0.4,0.5,0.05,0.3,0.1]) x 0.5

The 0.5 multiplier is a hyperparameter, although the ratio inside the array is well balanced, so a 0.5 adjustment may be needed.

As the same weights are reused over multiple timesteps, the same individual dropped weights remain dropped for the entirety of the forward and backward pass. The result is similar to variational dropout, which applies the same dropout mask to recurrent connections within the LSTM except that the dropout is applied to the recurrent weights. DropConnect could also be used on the nonrecurrent weights of the LSTM [Wi , Wf , Wo ].

ULMFit

A three-layer LSTM (AWD-LSTM) architecture with tuned dropout parameters outperformed other text-classification tasks trained using other training methods. Three techniques have been used to prevent over-catastrophic forgetting when fine-tuning is performed since the original pretrained model was trained on wiki-text103 and the dataset we will be dealing with is IMDb movie review.

Slanted Triangular Learning Rate (STLR)

My earlier experience involved using the Adam optimization algorithm with weight decay. But adaptive optimizers have limitations. If this model gets stuck in a saddle point and the gradients being generated are small, then the model has a hard time generating enough gradient to get out of a nonconvex region.

Cyclical learning rate, as proposed by Leslie Smith, addresses the issue. After using cyclical learning rate (CLR), 10% increment was seen in accuracy (CMC) in my work. For more, see this paper: Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks.

The learning rate determines how much of the loss gradient is to be applied to the current weights to move them in the direction of loss. This method is similar to stochastic gradient with warm restarts. Stochastic Gradient Descent with Restarts (SGDR) was used as the annealing schedule.

In a nutshell, choosing the starting learning rate and learning-rate scheduler can be difficult because it’s not always evident which will work better.

Adaptive learning rates are available for each parameter. Optimizers like Adam, Adagrad, and RMSprop adapt to the learning rates for each parameter being trained.

The paper Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks resolves many commonly faced issues in an elegant, simplified manner.

Cyclical Learning Rate (CLR) creates an upper and lower bound for value for learning rate. It can be coupled with adaptive learning methods but is similar to SGDR and is less computationally expensive.

If stuck in a saddle point, a higher learning rate can get the model out, but if it’s low as convention says (in later stages we are required to reduce learning rate), then traditional learning-rate-scheduler methods would never generate enough gradient if it gets stuck in elaborate plateau (non convex).

Non convex function

Non convex function

A periodic higher learning rate will have smoother and faster traversal over the surface.

The optimal learning rate (LR) would lie in between the maximum and minimum bounds.

Bounds being created by Cyclical Learning Rate

Bounds being created by Cyclical Learning Rate

Varying the LR in such a manner guarantees that this issue is resolved if needed.

So with transfer learning, the task is to improve performance on Task B given a model trained for static Task A. A language model has all the capabilities that a classification model in CV would have in the context of NLP: it knows the language, understands hierarchical relationships, has control over long-term dependencies, and can perform sentiment analysis.

Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification (ULMfit) has three stages, just like computer vision.

Three stages of ULMFit

Three stages of ULMFit

In first stage, LM pretraining (a), the language model is trained on a general dataset from which it learns general features of what language is and gathers knowledge of semantic relationships among words. Like ImageNet, this model uses wikitext103 (103 M tokens).

In second stage, LM fine-tuning (b), fine-tuning is required to the backbone (base model) using discriminative fine-tuning and using slanted triangular learning rates (STLRs) to make the model learn task-specific features.

In third stage, classifier fine-tuning (c), modifications are made to the classifier to fine-tune on a target task using gradual unfreezing and STLR to preserve low-level representations and adapt to high-level ones.

In a nutshell, ULMfit can be considered as a backbone and a classifier added over the top (head). It makes use of a pretrained model that has been trained on a general domain corpus. (Usually datasets that researchers deal with must be reviewed so as not to have many domain gaps.) Fine-tuning can be done later on a target task using mentioned techniques to produce State of the Art performance in text classification.

Problems Being Solved by ULMfit

This method can be called universal because it is not dataset-specific. It can work across documents and datasets of various lengths. It uses a single architecture (in this case AWD-LSTM, just like ResNets in CV). No custom features must be engineered to make it compatible with other tasks. It doesn’t require any additional documents to make it work across certain domains.

This model can further be improved with using attention and adding skip connections wherever necessary.

Discriminative Fine-Tuning

Each neural-net layer captures different information. In CV, initial layers capture broad, distinctive, wide features. With depth, they try to capture task-specific, complex features. Using the same principle, this method proposes to fine-tune different layers of this language model differently. To do that, different learning rates must be used for each layer. That way people can decide how the parameters in each layer are being updated.

The parameters theta were split into a list and that would parameters of l-th layer , and similarly the same operation can be done with learning rate as well . The stochastic gradient descent can then be run with discriminative fine-tuning:

Classifier Fine-Tuning for Task Specific Weights

Two additional linear blocks have been added. Each block uses batch normalization and a lower value of dropout. (Batch normalization causes a regularizing effect.) In between blocks, a rectified linear unit (ReLU) is used as activation function, and then logits are being passed on to softmax that outputs a probability distribution over target classes. These classifier layers do not inherit anything from pre-training; they are trained from scratch. Before the blocks, pooling has been used for last hidden layers and that is being fed to first linear layer.

trn_ds = TextDataset(trn_clas, trn_labels)

val_ds = TextDataset(val_clas, val_labels)

trn_samp = SortishSampler(trn_clas, key=lambda x: len(trn_clas[x]), bs=bs//2)

val_samp = SortSampler(val_clas, key=lambda x: len(val_clas[x]))

trn_dl = DataLoader(trn_ds, bs//2, transpose=True, num_workers=1, pad_idx=1, sampler=trn_samp)

val_dl = DataLoader(val_ds, bs, transpose=True, num_workers=1, pad_idx=1, sampler=val_samp)

md = ModelData(PATH, trn_dl, val_dl)

dropouts = np.array([0.4,0.5,0.05,0.3,0.4])*0.5

m = get_rnn_classifer(bptt, 20*70, c, vs, emb_sz=em_sz, n_hid=nh, n_layers=nl, pad_token=1,

layers=[em_sz*3, 50, c], drop=[dropouts[4], 0.1],

dropouti=dropouts[0], wdrop=dropouts[1], dropoute=dropouts[2], dropouth=dropouts[3])

PyTorch with FastAI API (Classifier Training)*

Concat Pooling

Often it’s important to take care of the state of the recurrent model and to keep useful states and release those which aren’t useful since there are limited states in memory to make updates with update gate. But the last hidden state generated from the LSTM model contains a lot of information, and those weights must be saved from the hidden state. To do that, we concatenate the hidden state of the last time step with the max and mean pooled representation of the hidden states over many timesteps as long as it can conveniently fit on GPU memory.

trn_dl = DataLoader(trn_ds, bs//2, transpose=True, num_workers=1, pad_idx=1, sampler=trn_samp)

val_dl = DataLoader(val_ds, bs, transpose=True, num_workers=1, pad_idx=1, sampler=val_samp)

md = ModelData(PATH, trn_dl, val_dl)

Training the Classifier (Gradual Unfreezing)

Fine-tuning the classifier straightway leads to overcatastrophic forgetting. Fine-tuning it slowly leads to overfitting and convergence. It’s recommended not to fine-tune the layers all at once but rather to fine-tune one at a time (freezing some layers in one go). Since last layer possesses general domain knowledge. The last layer is unfrozen afterwards, and then we can fine-tune previously frozen layers in one iteration. The next lower frozen layer is unfrozen, and the process is repeated until all layers are fine-tuned and convergence is noted.

Backpropagation through Time (BPTT) for Text Classification

Backpropagation through time (BPTT) is often used in RNNs to sequence data. BPTT works by unrolling all time steps. Each time step contains one input, one copy of the network, and one output. Errors generated by the network are calculated and accumulated at each time step. The network is rolled back up and weights are updated by gradient descent.

This model is initialized with the final state of the previous batch. Hidden states for mean and max pooling are also tracked. At the core, backpropagation uses variable-length sequences. Here is a snippet of Sampler being used in PyTorch:

This model is initialized with the final state of the previous batch. Hidden states for mean and max pooling are also tracked. At the core, backpropagation uses variable-length sequences. Here is a snippet of Sampler being used in PyTorch:

class SortishSampler(Sampler):

def __init__(self, data_source, key, bs):

self.data_source,self.key,self.bs = data_source,key,bs

def __len__(self): return len(self.data_source)

def __iter__(self):

idxs = np.random.permutation(len(self.data_source))

sz = self.bs*50

ck_idx = [idxs[i:i+sz] for i in range(0, len(idxs), sz)]

sort_idx = np.concatenate([sorted(s, key=self.key, reverse=True) for s in ck_idx])

sz = self.bs

ck_idx = [sort_idx[i:i+sz] for i in range(0, len(sort_idx), sz)]

max_ck = np.argmax([self.key(ck[0]) for ck in ck_idx]) # find the chunk with the largest key,

ck_idx[0],ck_idx[max_ck] = ck_idx[max_ck],ck_idx[0] # then make sure it goes first.

sort_idx = np.concatenate(np.random.permutation(ck_idx[1:]))

sort_idx = np.concatenate((ck_idx[0], sort_idx))

return iter(sort_idx)

So the Sampler returns an iterator (a simple object that can be iterated upon). It traverses the data in randomly ordered batches that are approximately of the same size. In the first call, the largest possible sequence is used, allowing proper memory-allocation sequencing.

Results

This method works phenomenally better than any other methods that relied on embeddings or some form of transfer learning in NLP research. After gradually unfreezing and training the classifier with novel methods (as discussed), it was easy to achieve an accuracy of 94.4 in just four epochs, beating other state of the art accuracies up to date.

Table 1. Loss and accuracies on Text Classification with ULMFit

Table 1. Loss and accuracies on Text Classification with ULMFit